Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Healing the Wounds of Data Misuse and Building Better Data Futures

Dr. Katharina Ruckstuhl doesn’t care much for slideshows, but she is a fan of using props when she presents.

During her talk for the Native Nations Institute’s International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Speaker Series at the BIO5 Institute’s Keating Building on September 27, 2022, Dr. Ruckstahl, Associate Professor at the University of Otago in Aotearoa (New Zealand), pulled a small black box from her purse and placed it on the table in front of her.

Inside the box was a bottle of perfume from a company called Mea Fragrance. Made from sustainably harvested leaves from the Taramea plant, which is native to the Southern Alps of Te Wai Pounamu (Aotearoa’s South Island), the fragrance has a two-century-long history with Aotearoa’s Ngāi Tahu population – the principle Māori iwi (Tribe) of the South Island – who used it as currency in trade and as gifts between chiefs.

Ruckstahl, who is of Ngāi Tahu and Rangitāne descent, says that the product represents the ethical use of Indigenous knowledge because the company that produces it exists as a means of preserving Māori cultural heritage. The company also distributes all proceeds from sales of their products “back to those who need it within Aotearoa,” according to their Facebook page.

But, for every example of an ethical use of data and/or knowledge gathered from Indigenous peoples, there are countless examples of data that was harvested at the expense of the Native subjects and/or tribes that provided it, or that was otherwise used extractively without the consent of the Indigenous subjects involved.

Misuse Breeds Mistrust

According to a recent paper published in the journal Frontiers in Genetics by Stephanie Russo Carroll and her research team at the Udall Center’s Native Nations Institute, “Indigenous Peoples have historically been targets of extractive research that has led to little to no benefit (for the people being studied).”

Well-known examples of this type of research include:

- a genetic study on diabetes focused on the Havasupai Tribe by Arizona State University that led to the unauthorized reuse of blood samples for additional studies on schizophrenia, inbreeding and human population migration theories, with the latter leading to the refutation of the Tribe’s traditional origin story. The unauthorized reuse of blood samples eventually led to a lawsuit and the return of those samples to the Havasupai Tribe.

- a study of arthritis amongst the Nuu-cha-nulth population in Canada that ended with the initial report getting shelved without any findings being presented to the Tribe or human subjects involved. That study’s principal researcher then reused the original blood samples in subsequent projects and even loaned them out to other researchers without the consent of the original subjects for additional studies on things like HIV, population genetics, and more.

- a study on alcohol use among Native subjects in Barrow, Alaska, the results of which cast a negative light on the population being studied as “alcoholic, and therefore facing extinction,” according to a write up by the New York Times. The researcher in question shared the study’s results with the subjects and press simultaneously, leaving the participants shaken and disenfranchised as their community was stigmatized on a national scale.

Far too numerous to detail here, research in both the public and private spheres is rife with examples of the unethical use of Indigenous data throughout history.

The result of that repeated misuse is a healthy distrust of researchers and research institutions, in general, amongst Indigenous populations the world over. So much so that Māori scholar Linda Smith calls research “one of the dirtiest words in the Indigenous world’s vocabulary” in her book, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples.

Not surprisingly, this has created a reticence or outright lack of willingness by many Native Nations and peoples to participate in research efforts if it is unclear how their participation will benefit the subject(s) of that research.

Moving from ‘FAIR’ data to data that ‘CAREs’

So, what does the ethical management of Indigenous data look like?

To help answer this question, Carroll and her team outlined a framework to guide researchers on how to employ more inclusive research principles when working with Indigenous subjects and nations.

In addition to the FAIR principles published in the journal Scientific Data in 2016 which held that data should be made Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, the NNI team published their CARE principles for Indigenous data governance in the Data Science Journal in 2020.

According to that paper, on top of making data more researcher friendly – which, ostensibly, was the purpose behind creating the FAIR principles – the CARE principles hold that researchers should also provide Collective benefit to the subjects in question, subjects should have the Authority to control their own data, and that data should be gathered and managed Responsibly and Ethically.

Few project review boards outside of those created by Tribal governments currently incorporate CARE principles as a standard for approving research projects that intend to examine Indigenous human subjects, however, meaning that it’s left to individual researchers to ensure that their work meets this ethical standard.

Indigenous Data Sovereignty Speaker Series

To help researchers better understand the role they play in the ethical management of Indigenous data today, and to offer a glimpse at the path to ensuring all research projects involving Indigenous human subjects meet the standards outlined by the CARE principles, the Udall Center’s Native Nations Institute partnered with UArizona’s BIO5 Institute this year to host a series of talks featuring international thought leaders in the field of Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

The first three presentations in that series included a conversation about data ownership and the ethical use of data by Katharina Ruckstahl, a look at the importance and process of standard setting for ethical research at the highest levels with University of Tasmania Distinguished Professor Emerita Dr. Maggie Walter (Palawa from Lutruwita/Tasmania), and a close examination of one project that meets the CARE principle standard – the Mayi Kuwayu Study – by Australian social epidemiologist Dr. Ray Lovett (Wongaibon) and his research team.

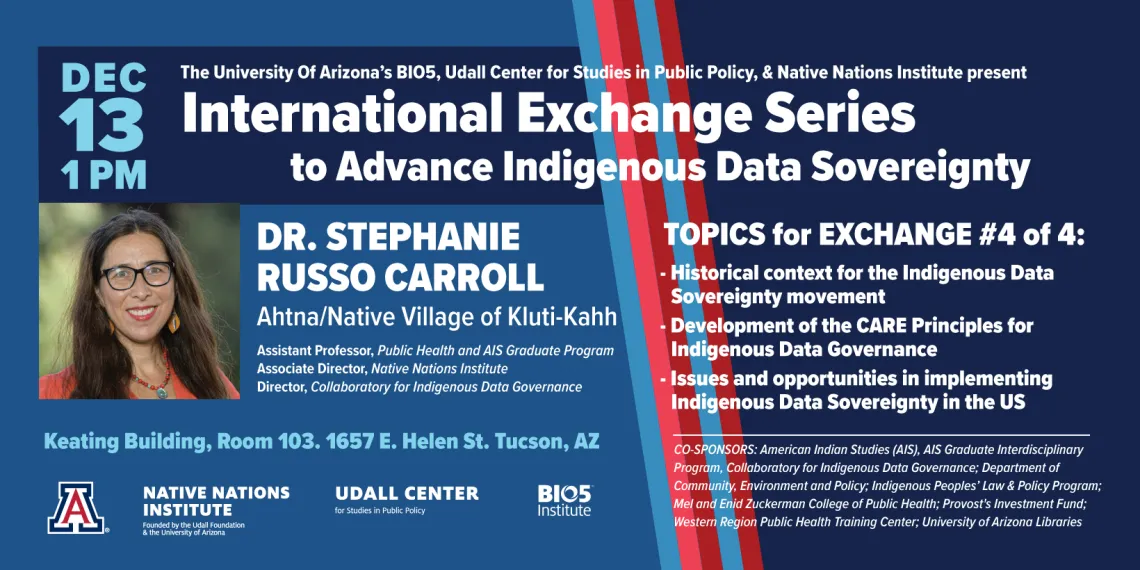

The fourth and final presentation in the series will take place on Tuesday, December 13 at the BIO5 Institute. During that talk, titled “Indigenous Data Sovereignty: principles and practice in the US experience”, Drs. Stephanie Russo Carroll and Ibrahim Garba from the Native Nations Institute will further unpack themes from the previous three events by addressing challenges and opportunities for institutional change in the US context.

Attending the event is a great way for researchers interested in pursuing projects that might involve Indigenous human subjects and nations to gain familiarity with this emerging field and to ensure that they are holding themselves to the highest ethical standards in their work with Indigenous data and knowledge.

The event will feature both in-person and remote registration options.

Take A 3-Day Course During January in Tucson 2023:

Indigenous Data Governance

with Stephanie Russo Carroll, DrPH, and Felina Cordova-Marks, DrPH

Indigenous Data Sovereignty

with Desi Small-Rodriguez, PhD

Indigenous Research Governance

with Ibrahim Garba, PhD, and Dominique David-Chavez, PhD

Images featuring: Stephanie Carroll Russo, Katharina Ruckstuhl, Lori Schultz (Assistant Vice President, Research Intelligence), Jennifer Kehlet Barton (Director, BIO5 Institute)